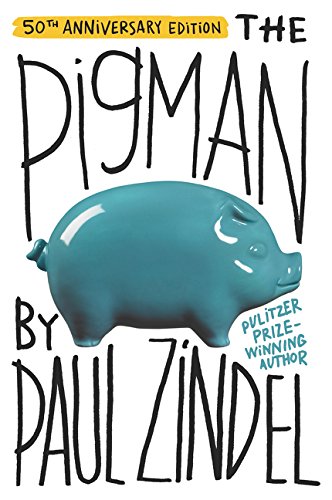

음... 일단 이 책을 10년만에 다시 읽어본 소감을 나열하자면...

1) 어릴 땐 존이 엄청 웃긴 애인 줄 알았다 (사실 얘 말투 멋모르고 따라하다가 결국 정신상태가 개차반이 되었다). 지금은 여전히 웃기긴 한데 (그리고 잘생겨서 루피 표정 짓게 만듦ㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋ) 내가 여기 나오는 모든 등장인물들을 대신해서 한 대 갈겨주고 싶은 생각이 자주 들었다. 이 놈이 자꾸 뺀질거리면서도 자기가 불행한 가정에서 자라서 그렇다는 식으로 합리화를 하는데, 이런 합리화가 계속되면 결국은 콩밥 먹으면서도 정신 못 차리고 남의 탓 하게 됩니다... 뭐 기억 속의 2편 줄거리를 생각해 보면 피그맨과 헤어진 뒤로 많이 철이 든 듯 합니다만... 여기선 일단 너무 사고뭉치라 때리고 싶음.

2) 로레인의 어머니는 피해망상증이 있는 것처럼 묘사되는데, 요즘 같은 시대엔 저러지 않는 게 오히려 더 이상하다는 생각이 들면서 자꾸 이해가 갔다.... (적어도 로레인의 어머니는 손정우가 솜방망이 처벌을 받는 시대에 살지는 않았다)

3) 존과 로레인이 왜 이렇게나 죄책감에 시달리는 건가 싶었는데 다시 읽으니까 피그맨의 최후가 너무나도 처참해서 나였어도 누군가를 그런 지경까지 몰아넣고 나면 트라우마에 빠질 것 같다.

4) 결말! 어딘가 찜찜하고 난해하다고 느꼈던 결말이 지금 보니까 가슴아플 정도로 와닿았다. 이 세상 모든 소설을 통틀어서 성장의 과정을 가장 냉정한 관점에서 표현한 작품이 아닐까 생각한다.

아마존에 폴 진델 소설이 많이 들어와서 조만간 피그맨 후속작도 다시 읽어보고 다른 소설들도 봐야겠다. 참고로 국내에 들어온 피그맨 번역본은 비룡소 출판사에서 번역한 건데 원작에서 자주 보이는 존의 시니컬한 농담이나 소설 전반의 분위기를 자연스럽게 잘 옮겨서 지금까지도 최고의 번역본 중 하나로 손에 꼽고 있다.

Actually, I hate school, but then again most of the time I hate everything.

(이건 내가 생각하는 소설 속 최고의 첫문장 top 10에 반드시 들어가야 하는 문장. 솔직히 이게 롤리타의 라잇오브마랖보다 더 강렬하다고 생각한다.. ㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋ)

Every one of the fruit rolls was successful, except for the time we had a retired postman for General Science 1H5. We were supposed to study incandescent lamps, but he spent the period telling us about commemorative stamps. He was so enthusiastic about the old days at the P.O. I just didn’t have the heart to give the signals, and the kids were a little put out because they all got stuck with old apples.

She finally said I could curse if it was excruciatingly necessary by going like this @#$%. Now that isn’t too bad an idea because @#$% leaves it to the imagination and most people have a worse imagination than I have. So I figure I’ll go like @#$% if it’s a mild curse—like the kind you hear in the movies when everyone makes believe they’re morally violated but have really gotten the thrill of a lifetime.

And as you probably suspected, the reason John gets away with all these things is because he’s extremely handsome. I hate to admit it, but he is. An ugly boy would have been sent to reform school by now. He’s six feet tall already, with sort of longish brown hair and blue eyes. He has these gigantic eyes that look right through you, especially if he’s in the middle of one of his fantastic everyday lies. And he drinks and smokes more than any boy I ever heard of.

I tried to explain to him how dangerous it was, particularly smoking, and even went to the trouble of finding a case history similar to his in a book by Sigmund Freud. I almost had him convinced that smoking was an infantile, destructive activity when he pointed out a picture of Freud smoking a cigar on the book’s cover.

“If Freud smokes, why can’t I?”

“Freud doesn’t smoke anymore,” I told him. “He’s dead.”

If I made a list of every comment she’s made about me, you’d think I was a monstrosity. I may not be Miss America, but I am not the abominable snowwoman either.

I really hate it when a teacher has to show that she isn’t behind the times by using some expression which sounds so up-to-date you know for sure she’s behind the times.

If anyone distorts, it’s that mother of hers. The way her old lady talks you’d think Lorraine needed internal plastic surgery and seventeen body braces, but if you ask me, all she needs is a little confidence. She’s got very interesting green eyes that scan like nervous radar—that is they used to until the Pigman died. Ever since then her eyes have become absolutely still, except when we work on this memorial epic. Her eyes come to life the second we talk about it.

“Do you realize I’ve been trying to get your mother for an hour and a half and the line’s been busy?”

Bore bellowed.

“Those things happen. I was talking to a friend.”

“If you don’t use the phone properly, I’m going to put a lock on it.”

“Yeah? No kidding?”

Now it was just the way I said yeah that set him off, and that night when he got home, he just put the lock on the phone and didn’t say a word. But I’m used to it. Bore and I have been having a lot of trouble communicating lately as it is, and sometimes I go a little crazy when I feel I’m being picked on or not being trusted. That’s why I finally put airplane glue in the keyhole of the lock so nobody could use the telephone, key or no key.

Actually, Norton is a social outcast. He’s been a social outcast since his freshman year in high school when he got caught stealing a bag of marshmallows from the supermarket. He never recovered from that because they put his name in the newspaper and mentioned that the entire loot was a bag of marshmallows, and ever since then everybody calls him The Marshmallow Kid. “How’s The Marshmallow Kid today?”

You might also be interested in knowing that the only part of Johnny Tremain that John did end up reading was page forty-three—where the poor guy spills the molten metal on his hand and cripples it for life. That was the part he finally did his book report on—just page forty-three—and he got a ninety on it! I only got eighty-five, and I read the whole thing.

You have to know how demented Dennis and Norton are to understand that when I told them Angelo Pignati caught on Lorraine was a phony and hung up, they believed it. I could tell them I went alligator hunting in St. Patrick’s Cathedral last night, and they’d believe it.

I blame an awful lot of things on the ghost of Aunt Ahra because she died in our house when she was eighty-two years old. She was really my father’s mother’s sister, if you can figure that one out, and she had lived with us ever since the time she took a hot bath in her own apartment and couldn’t get out of the bathtub for three days. They found her when she finally managed to throw a bottle of shampoo through the bathroom window, and it splattered all over the side of a neighbor’s house. The neighbor thought it was the work of a juvenile delinquent at first, which is sort of funny if you think about it awhile.

“Yes?” “Hello, operator? Would you please get me Yul-1219?” “You can dial that number yourself, sir.” “No, I can’t. You see, operator, I have no arms.” “I’m sorry, sir.” “They’ve got this phone strapped to my head for emergency calls, so I’d appreciate it if you’d connect me.” “I’ll be happy to, sir.”

“You read all those books, and you don’t even know when a man is thinking about committing suicide.”

“Stop it, John.”

“You think I’m kidding?”

“He did not sound like he was thinking of suicide.”

“You only know about the obvious kind—like when someone’s so desperate they’re going to jump off a bridge or slit their wrists. There are other kinds, you know.”

“Like what?”

“Like the subconscious kind. You’re always blabbing about the subconscious, and you can’t even tell a subconscious suicide when you talk to one.”

She started biting her lip again.

“He sounded just like the kind of guy who’d commit suicide by taking a cold shower and then leaving the windows open to die of pneumonia!”

Well, actually I might as well tell you we were both scared stiff when he went into the kitchen. At first he seemed too nice to be for real, but when I looked at Lorraine and she looked at me, I could tell we both were thinking what we’d do if Mr. Pignati came prancing out of the kitchen with a big knife in his hand. He could’ve been some psycho with an electric carving knife who’d dismember our bodies and wouldn’t get caught until our teeth clogged up the sewer or something like that. I mean, I thought of all those things, and I figured if he did come running out with a knife, I’d grab hold of the ugly table lamp right next to me and bop him one on the skull. I mean, if you’re going to survive nowadays, you really have to think a bit ahead.

이것도 내가 생각하는 명문장 ㅋㅋㅋㅋ

“Touch them,”

he told her.

“Don’t be afraid to pick them up.”

It was a big change from my mother who always lets out a screech if you go near anything, so I couldn’t help liking this old guy even if he was sort of weird.

The thing that made me stop going to the zoo a few years ago was the way one attendant fed the sea lions. He climbed up on the big diving platform in the middle of the pool and unimaginatively just dropped the fish into the water. I mean, if you’re going to feed sea lions, you’re not supposed to plop the food into the tank. You can tell by the expressions on their faces that the sea lions are saying things like

“Don’t dump the fish in!”

“Pick the fish up one by one and throw them into the air so we can chase after them.”

“Throw the fish in different parts of the tank!”

“Let’s have fun!”

“Make a game out of it!”

John had gotten bored with Bobo and moved down to the next cage that had a gorilla. He was imitating Tarzan and going AaaaaaaaayaaaaaaaaaH!—which I don’t think was the most original performance that gorilla had ever seen. Can you imagine what gorillas must think after being in a zoo a few years and hearing practically every boy who comes to look at them go AaaaaaaayaaaaaaaaH? If that isn’t enough to give an animal paranoia, I don’t know what is.

Then John decided to strike up a conversation with the gorilla. Only the gorilla started to make these terrifying noises, and John started to make believe he was a monkey and began screaming back at the gorilla.

He bought me two cotton-candies-on-a-stick, one bag of peanuts, and a banana split at this homemade ice-cream palace. Lorraine got at least four bags of peanuts, one cherry ice-cream cone, and a black-and-white soda. If you let her, Lorraine would eat until she dropped, and if she keeps going at that rate, I’m afraid she’s going to be somewhat more than voluptuous. She could end up just plain fat.

Once I ran away from Lorraine and the others and hid in a part of the cemetery that didn’t have perpetual care. That’s the part where no one pays to keep the grass cut. I was just lying on my back, looking up at the stars, and I was so loaded I thought I could feel the spin of the earth. All those stars millions of light years away shining down on me—me glued to a minor planet spinning around its own gigantic sun. I stretched out and touched stone. I remember pulling my hands back to my sides, just keeping my eyes on the stars, concentrating on bringing them in and out of focus.

“Is there anyone up there trying to talk to me? Anybody up there?”

“Anybody down there?” If I was lying on somebody’s grave, whoever it was would be six feet away. Maybe there had been a lot of erosion, and whoever it was was only five feet away… or four. Maybe the tombstone had sunk at the same rate as the erosion, and the body was only a foot away below me—or an inch. Maybe if I put my hand through the grass, I would feel a finger sticking out of the dirt—or a hand. Perhaps both arms of a corpse were on either side of me right at that moment. What could be left? A few bones. The skull. The worms and bacteria had eaten the rest. Water in the earth had dissolved parts, and the plants had sucked them up. Maybe one of the molecules of iron from the corpse’s hemoglobin is in the strand of grass next to my ear. But the embalmers drain all the blood—well, probably not every drop. Nobody does anything perfectly. Then I got very sad because I knew I wasn’t really wondering about the guy underneath me, whoever he was. I was just interested in what was going to happen to me. I think that’s probably the real reason I go to the graveyard. I’m not afraid of seeing ghosts. I think I’m really looking for ghosts. I want to see them. I’m looking for anything to prove that when I drop dead there’s a chance I’ll be doing something a little more exciting than decaying.

I just couldn’t smile at his joke. I thought it was very sad. I mean, that cute little girl in the ruffled dress had already grown up, gotten married, lived her life, and was underground somewhere. And Mr. Pignati wasn’t able to admit it. That landlady used to think her husband was going to come back one day too, but she died less than two months after him. I’ve always wondered about those cases where a man and wife die within a short time of each other. Sometimes it’s only days. It makes me think that the love between a man and a woman must be the strongest thing in the world.

Mr. Pignati said he’d meet us there after he had stopped at the zoo to feed Bobo, which was fine with John. He loves to wait for people in the ferryhouse because all the bums and drunks come over. He really drives them crazy. They’ve got drunks and bums all over the Staten Island ferryhouse, but not half as many as they’ve got on the other side at South Ferry. John makes them tell their whole life story before he’ll give them a nickel.

This one bum who came over said his name was Dixie. Everybody called him Dixie because he came from the South. Then he told this story about how he used to be a professor at Southern Pines University, but he took some LSD as part of an experimental program and lost his power of concentration. His whole academic life had come to an end because he’d lost his power of concentration. I thought of writing a story about him until John told me the same bum had come up to him a month ago and said his name was Confederate. He said they called him that because he was from the South. John said he told an entirely different story—about how he had been taking a speed-reading course and he was reading faster than anybody in the world. He said he used to read so fast he had to buy two copies of every book and cut the pages out and put them on tables around the room, and then he’d run by the pages. That’s how fast he could read. He said he was written up in Scientific American magazine in the January, 1949, issue, and anybody could check it out. He was supposed to have a sister in Marlboro, Vermont, who could do the same thing. And then the tragedy was supposed to have happened. He was running around the room so fast he banged into a table and lost his power of concentration.

It’s sort of spooky how when you’re caught talking to God nowadays everybody thinks you’re nuts. They used to call you a prophet.

“Now you pick out some things you’d like to try.”

He smiled at me. John had already picked out a carton of tiger’s milk and a box of chocolate-covered ants. Ugh. Anything to be weird.

“Why not?”

John had to ask.

“Because I told you not to, that’s why.”

Now that’s the kind of logic that really sets John off. That floorwalker could have simply said that monkeys bite or that popcorn is not their natural diet or something like that—but instead he had to think he was a schoolteacher. From that moment on, every time the floorwalker half turned his back John made believe he was throwing popcorn into the monkey cage, and I thought that man was going to go insane.

“John, are you crazy?”

Just as the words came out of my mouth I could tell from the fallen expression on his face that if I didn’t wear the roller skates, I’d be letting him down. I’d be disappointing him in the main thing that he liked about me. I—and maybe now even the Pigman—were the only ones he knew who could understand that doing something like roller-skating out of Beekman’s was not absolutely crazy. Everything in his home had to have a purpose. There was no one there who could understand doing something just for fun—something crazy—and that was what he’d liked about me from that first day when I laughed on the bus and was just as crazy as he was.

Lorraine told you she thinks Norton and I hate each other. It’s true. Norton is so low on the scale of evolution he belongs back in the age of the Cro-Magnon man. Norton actually did play with dolls when he was a kid. That was his mother’s fault, just like in that “Dear Alice” column. When he was old enough to know better, he didn’t play with dolls anymore. But the kids used to make cracks about him, so that made him go berserk around the age of ten. He was the only berserk ten-year-old in the neighborhood. From then on he turned tough guy all the way. He was always picking fights and throwing stones and beating up everybody. In fact, he got so tough he used to go around calling the other guys sissies. When I was a freshman going through my Bathroom-Bomber complex, Norton was a specialist in the five-finger discount. He used to shoplift everywhere he went. It used to be small-time stuff like costume jewelry for his mother and candy bars and newspapers. Then he got even worse, until now his eyes even drift out of focus when you’re talking to him. He’s the type of guy who could grow up to be a killer.

“Well, what are you and that screech owl going over there for?”

“I told you not to call Lorraine a screech owl!”

“What if I feel like calling her a screech owl?”

I took a sip of my beer, which was as warm as @#$%, and then looked him straight in the face. I wasn’t scared of him because we were sort of evenly matched.

“I mean, what would you do about it?” Norton grinned.

“Oh, probably nothing,” I said, smiling back at him.

“Maybe I’d go buy some… marshmallows.”

The grin on Norton’s face faded away so quickly you’d think I just stuck a knife into him.

“You wouldn’t happen to know where I could buy some… marshmallows, would you?” I said, smiling.

“All right, I’m sorry I called her a screech owl,” Norton said, trying to avoid the unavoidable.

The smell of hospitals always makes me think of death. In fact I think hospitals are exactly what grave-yards are supposed to be like. They ought to bury people in hospitals and let sick people get well in the cemeteries.

Gary Friman, Barney Friman’s brother, played the drums. He was sort of the hero of the teen-age music world ever since he got drunk one night at a party last summer and played the drums in the middle of Victory Boulevard.

Melissa Dumas was there too because she goes steady with Gary Friman, and she always sings two songs with the band. She only sings two songs because that’s all she knows. She’s got a lovely voice, but her memory is like that of a titmouse with curvature of the brain.

Janice Dickery did this fantastic shaking that got everybody upset, with only Gary Friman on the drums. Like I told you, she’s very mature, and when she shakes, you can understand how come she had to drop out of school in her junior year.

The cat attacked the ball as if it were a living thing. I remember thinking it was practicing for when it might have to kill to survive. Play was something natural, I remember thinking—something which Nature wanted us to do to prepare us for later life.

But I did care. She thinks she knows everything that goes on inside me, and she doesn’t know a thing. What did she want from me—to tell the truth all the time? To run around saying it did matter to me that I live in a world where you can grow old and be alone and have to get down on your hands and knees and beg for friends? A place where people just sort of forget about you because you get a little old and your mind’s a bit senile or silly? Did she think that didn’t bother me underneath? That I didn’t know if we hadn’t come along the Pigman would’ve just lived like a vegetable until he died alone in that dump of a house?

“Do you think you’d like to go to the zoo with me tomorrow, Mr. Wandermeyer and Miss Truman.”

“Please….”

“Please.”

Didn’t she know how sick to my stomach it made me feel to know it’s possible to end your life with only a baboon to talk to? And maybe Lorraine and I were only a different kind of baboon in a way. Maybe we were all baboons for that matter—big blabbing baboons—smiling away and not really caring what was going on as long as there were enough peanuts bouncing around to think about—the whole pack of us—Bore and the Old Lady and Lorraine’s mother included—baffled baboons concentrating on all the wrong things.

Then I knew. I was not in a monkey house. For a moment it was something else—something I was glimpsing for the first time—the cold tiles, the draft that moved about me, the nice solid fact that someday I was going to end up in a coffin myself. My tomb.

I stayed until the ambulance doctor gestured that the Pigman was dead. A whole crowd of people had gathered to crane their necks and watch them roll a dead man onto a stretcher. I don’t know where they all came from so quickly. It must have been announced over the loudspeaker. Hey everybody! Come see the dead man in the monkey house. Step right up. Special feature today.

“Here’s your glasses,”

I said again, almost hating her for a second. I wanted to yell at her, tell her he had no business fooling around with kids. I wanted to tell her he had no right going backward. When you grow up, you’re not supposed to go back. Trespassing—that’s what he had done.

We looked at each other. There was no need to smile or tell a joke or run for roller skates. Without a word, I think we both understood. We had trespassed too—been where we didn’t belong, and we were being punished for it. Mr. Pignati had paid with his life. But when he died something in us had died as well. There was no one else to blame anymore. No Bores or Old Ladies or Nortons, or Assassins waiting at the bridge. And there was no place to hide—no place across any river for a boatman to take us. Our life would be what we made of it—nothing more, nothing less.

Baboons.

Baboons.

They build their own cages, we could almost hear the Pigman whisper, as he took his children with him.

'독서' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 그래, 이 맛에 사는 거지 / 커트 보니것 (0) | 2020.08.24 |

|---|---|

| The Collected Works of Scott McClanahan Vol. 1 / Scott McClanahan (0) | 2020.08.10 |

| 올랜도 / 버지니아 울프 (0) | 2020.07.15 |

| My Year of Rest and Relaxation / Ottessa Mosefegh (0) | 2020.07.08 |

| 전쟁은 여자의 얼굴을 하지 않았다 / 스베틀라나 알렉시예비치 (0) | 2020.07.08 |